Mystery of the Lascaux caves

General

While en route to the 18,000-year-old Lascaux caves, I was wondering what vestiges of our 21st century civilization will be found by the human beings of the future. Miniaturized circuits, layers of polymer, radioactive waste, gutted mines, detritus from satellites? How will those people decipher our artefacts? As the traces of an ancient fallen civilization? Or as the prelude to the downfall of human intelligence?

LeVerbe - by Sarah-Christine Bourihane (Translated by the Archdiocese of Montreal)

Listening to the GPS as it gives me directions to this prehistoric site, the juxtaposition is jarring. The instantaneous-response technology that characterizes our culture could never have come about, had it not been for the long, slow maturing over time of human intelligence as it contemplated by candlelight its own condition or marvelled at the brightness of a fire. Standing in front of these works of art from an entirely different time scale, I am overwhelmed. And yet this empire of the ephemeral in which we live is also a part of a vast and coherent continuum.

Homo erectus rises up and considers the stars. The Neanderthal ignites the fire. Sapiens wander the earth, bury their dead and paint on rock surfaces. What can these first human beings teach us about ourselves hundreds of millennia later?

Video in French only

Art for art’s sake

On a hot summer’s day in the modern-day French département of the Dordogne, it is difficult to imagine hunter-gatherers going about their lives in the climatic conditions that prevailed in the last Ice Age, with temperatures of minus 20°C in winter and plus 15°C in summer. In the region of the Vézère river, Cro-Magnon man eked out an existence clothing himself in reindeer skins and finding shelter, when not contending with herds of dangerous animals.

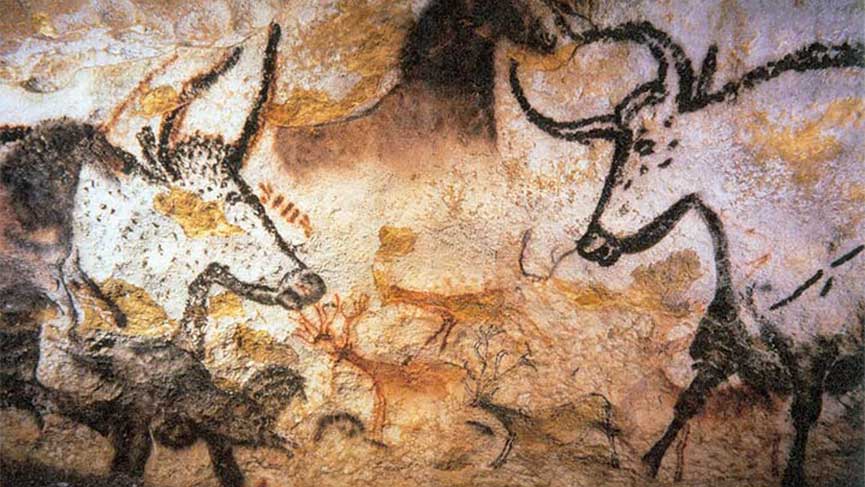

Even amid such conditions, certain individuals turned their energies to an activity unrelated to the struggle to survive. Leaving that reality behind, they made paintings, by the light of a lantern, underground, in a place where the cycles of sun and moon no longer existed. Within this shelter away from time, and unaware of the significance of their acts, these men immortalized the first infant impulses of art for the hundreds of thousands of years to come.

The phenomenon was not unique to Lascaux, as similar rock paintings have been found in caves on all five continents. Dating from approximately 40,000 to 10,000 B.C., they depict hands and animals, rendered with precision usually, and just a few human figures with indistinct features. Tribe after tribe, separated by immense expanses, traced the rudiments of one symbolic vision on walls of rock.

Homo religiosus

From the Paleolithic era, nothing was documented illustrating prehistoric man’s beliefs. Their thoughts remain a mystery, giving rise to speculation on various hypotheses.

Historian of religion Mircea Eliade proposed that the sacred is the basis of human consciousness, as opposed to something acquired during the course of our development. In other words, for Eliade, Homo sapiens – he who knows that he knows – is fundamentally a religious being. The writer’s theses are contested, but disproving them is an arduous task.

We do know, however, that around 100,000 B.C., people were making burial places. Bodies buried in particular positions or accompanied with objects or daubed with red ochre, the colour of blood and hence a symbol of life, these are all evidence of an early belief in life after death.

It was not merely to record the day-to-day lives of hunter-gatherers that cave paintings were created, according to Eliade. These paintings symbolized facets of life for paleolithic man: “the habits of his prey, sexuality, death, the mysterious powers of supernatural elements and personages.” Beyond being simply a drawing of this or that individual animal, these paintings, he submits, reflect a system of beliefs.

Is it possible that the Lascaux caves, sometimes called the Sistine Chapel of prehistory, served as a temple for the assembled tribe to recount – or recreate – their genesis myths? Were these caves a sacred place where the spirits of animals were invoked in supplication for a good hunt? Theories respecting shamanism are plausible, since ethnographic parallels can be seen in the beliefs of hunter-gatherers as a group, as distinct from those of later sedentarized peoples practising agriculture.

A poetic approach

French author Jean Rouaud is fascinated by prehistory and has written extensively on the subject. He finds that poetry is an effective method to use in approaching this era of human existence. In an interview with the magazine La vie, Rouard experiments with an exercise whereby he attempts to enter into the mind of a paleolithic man.

“The motives for our actions are not merely economic considerations. We are also driven by symbolic motives. In a glacial climate and with very little vegetation around, one can see for great distances. Huge herds move about. The power of the mammoth is evident, as is the strength of the bull, the speed of the horse. Man identifies with them,” suggests Rouard; “Man envies the animals.”

During the Mesolithic, there arose a new relationship between man and animal. The earth was now completely forested. The vast herds had disappeared from the landscape and, as animals were less and less present in the art in the rock wall representations, the scene became increasingly occupied by man.

Then, in the Neolithic, the human figure is shown bringing down animals with bows and arrows. “Now man can assert himself as master and owner of nature;” imagines the writer, “He has invented agriculture, he cultivates grains, he moves enormous stones from one place to another.”

Return to a state of wonder

Historically, the menhirs and the dolmens came first, followed by the pyramids and then the temples, and after all of these, the cathedrals. In this entire progression, Rouaud sees a downward tendency: “the cathedral is a grotto, sprung from the earth and filled with air; in the centre are flowers of light from the stained-glass windows. This was mankind’s last moment of wonder. After this, it is finished.”

Artificial intelligence is now actually producing works of art. The question is: what is human intelligence? So, let’s go back to the beginning, to those cavemen who laid aside their labours of subsistence in order to paint, to express their spiritual nature. We wonder at a child’s very first steps; its very first questions remind us of our extraordinary ancestors, and of this early art. There is no doubt: the splendour of intelligence precedes instrumental rationality, and eclipses it.

Comment

Comment

Add new comment